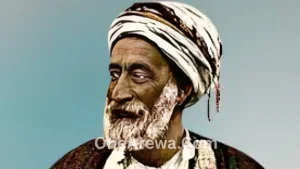

Shehu Usman Dan Fodio: The Islamic Scholar Who Founded the Sokoto Caliphate (1754–1817)

Shehu Usman Dan Fodio: The Islamic Scholar Who Founded the Sokoto Caliphate (1754–1817)

Shehu Usman Dan Fodio, born in December 1754 in Maratta, Gobir (present-day northern Nigeria), was a prominent Fulani Islamic scholar, philosopher, and spiritual reformer.

Between 1804 and 1808, he led a major Islamic revolution, often referred to as a jihad, that resulted in the establishment of the Sokoto Caliphate, one of the most powerful Muslim empires in West Africa.

He died in 1817 in Sokoto, the heart of the Fulani empire.

After leading a successful Islamic revolution, Usman dan Fodio was honored with the title “Amir al-Mu’minin” (Commander of the Faithful) by his followers, known as the Jama’a.

However, he humbly declined the throne and chose to continue his mission of preaching and teaching Islam.

Born in Gobir in December 1754, Usman dan Fodio came from the Torodbe clan, a group of educated and urbanized ethnic Fulani who had lived in the Hausa kingdoms since the 1400s.

From an early age, he was deeply rooted in Islamic studies and quickly became a respected preacher of Sunni Islam across what is now Nigeria and Cameroon.

His passion for reform led him to author over 100 books on religion, politics, governance, and society.

Usman fiercely criticized the ruling Muslim elites of his time, accusing them of corruption, idolatry, and failure to adhere to Sharia law.

In response, he launched a religious and social revolution from Gobir that soon spread across much of West Africa.

This movement not only overthrew unjust rulers but also laid the foundation for a new Islamic state.

In 1803, Usman founded the Sokoto Caliphate, and by 1804–1808, he had led a jihad that defeated many oppressive kings.

The caliphate eventually expanded its influence into present-day Northern Nigeria, Southern Niger, Cameroon, and Burkina Faso.

Rather than clinging to power, Usman handed political leadership to his son, Muhammad Bello, while he continued to mentor and correspond with other reformist leaders across Africa.

A strong advocate for education and literacy, Usman dan Fodio supported learning for both men and women.

Several of his daughters became well-known scholars and writers. To this day, his works and teachings are widely referenced in Nigeria, and he is affectionately remembered as “Shehu”, a term of reverence.

Usman Dan Fodio is considered by many to be a mujaddid, a divinely guided reformer of Islam.

His jihad was part of a larger wave of Islamic revival movements in West Africa during the 17th to 19th centuries, following earlier jihads in Futa Bundu, Futa Tooro, and Fouta Djallon.

He later inspired future Islamic leaders like Seku Amadu of the Massina Empire and Omar Saidou Tall of the Toucouleur Empire, the latter of whom married one of Usman’s granddaughters.

Shehu Usman Dan Fodio Profile

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Full Name | Usman bin Muhammad bin Uthman bin Salih bin Harun bin Gurdo bin Jabbo bin Muhammad Sambo |

| Popular Name | Shehu Usman ɗan Fodio |

| Birth Date | 15 December 1754 |

| Birthplace | Maratta, Gobir (present-day northern Nigeria) |

| Death Date | 20 April 1817 (aged 62) |

| Place of Death | Sokoto, Nigeria |

| Burial Site | Hubbare Shehu, Sokoto, Nigeria |

| Father | Muhammadu Fodio |

| Mother | Hauwa bint Muhammad |

| Spouses | Maimuna, Aisha (Gaabdo), Hawa’u, Hadiza |

| Children | 23 children, including Muhammad Bello, Nana Asma’u, Abu Bakr Atiku, Ahmadu Rufai |

| Title | Sarkin Musulmi (Commander of the Faithful) |

| Reign | 1803–1817 |

| Successor | Muhammad Bello (son) |

| Other Titles | Nūr al-Zamān (Light of the Age), Mujaddid al-Islām (Reviver of Islam) |

| Religion | Islam |

| Denomination | Sunni |

| Jurisprudence | Maliki |

| Creed | Ashʿari |

| Sufi Order | Qadiri |

| Achievements | Founder of the Sokoto Caliphate, leader of the 1804 jihad, promoted Islamic education |

| Writings | Over 100 books, 480 poems in Arabic, Fulfulde, and Hausa |

| Notable Works | Bayan Wujub al-Hijrah ‘ala al-‘Ibad, Kitab al-Farq, Diwan (poetry) |

| Legacy | Founder of Islamic governance in West Africa, inspired educational and political reforms |

| Popular Culture | Appears as a character in Age of Empires III: Definitive Edition (2020) |

Shehu Usman Dan Fodio’s Early Life

Lineage and Childhood:

Usman Danfodio, born on December 15, 1754, in Maratta (near the border of the Bornu and Songhai Empires), belonged to the Toronkawa clan, a lineage of Islamic scholars and preachers who began settling in Hausaland as early as the 1300s.

This migration, led by Musa Jokollo, Usman’s 11th great-grandfather, was part of a broader movement of wandering scholars who laid the foundations for Islamic learning in West Africa, long before the Sokoto Jihad.

The Toronkawa are said to have Arab ancestry through an individual named Uqba, who married a Fulani woman, Bajjumangbu.

While the exact identity of this Uqba remains debated (whether he was Uqba ibn Nafi, Uqba ibn Yasir, or Uqba ibn Amir), this connection is mentioned by Abdullahi dan Fodio, Usman’s brother, and other family members, including Muhammad Bello.

On Usman’s maternal side, his mother Hauwa is believed to be a direct descendant of Prophet Muhammad.

Hauwa was a descendant of Maulay Idris I, the first Emir of Morocco, and the great-grandchild of Hasan, the grandson of the Prophet.

This prestigious lineage was also confirmed by Ahmadu Bello, the first Premier of Northern Nigeria and a descendant of Usman dan Fodio.

Initially, the Toronkawa settled in Konni, a village on the border of the Bornu and Songhai Empires, but persecution forced them to move.

Usman’s great-grandfather, Muhammad Sa’ad, led the family to Maratta, where Usman was born.

Following Usman’s birth, his family relocated again to Degel, a town that became a center for Islamic learning and where Usman’s intellectual development would begin.

Usman’s father, Muhammad Fodio, was a respected Islamic scholar, revered for his profound knowledge.

Muhammad was given the title “Fodiye” (meaning “the learned one”), which later influenced Usman’s name, “dan Fodio”, meaning “son of Fodio”.

Usman often referred to his father’s teachings in his own writings, acknowledging the deep intellectual and spiritual influence his father had on him. Muhammad Fodio died in Degel and was buried there.

Usman’s mother, Hauwa, was his first teacher and came from a family deeply committed to learning.

Her mother, Ruqayyah bint Alim, was renowned as a teacher and ascetic.

Ruqayyah’s literary work, Alkarim Yaqbal, became popular among Islamic scholars in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Hauwa’s father, Muhammad bin Uthman bin Hamm, was widely regarded as one of the most knowledgeable Fulani clerics of the time.

Check Out: General Abdulsalami Abubakar: The Military Leader Who Brought Back Democracy to Nigeria (1998–1999)

Shehu Usman Dan Fodio Education and Scholarly Development

As a young boy, Shehu Usman Dan Fodio studied the Qur’an under the guidance of his father in Degel.

As his education progressed, he studied under other notable scholars, including Uthman Bn Duri and Muhammad Sambo.

However, his most influential teacher was Jibril bin Umar, a powerful intellectual and advocate of jihad.

Though the two would eventually disagree over certain theological points, Jibril had a significant influence on Usman’s early education.

At the age of 20, Usman established his own school in Degel, where he taught, preached, and continued his studies.

His scholarship rapidly advanced, and by 1786, he attended an academic assembly led by his cousin Muhammad bn Raji, where he received further academic recognition.

By 1787, Usman was already writing extensively. His books and long poems, primarily in Arabic and Fulfulde (Fulani), focused on Islamic reform and philosophy.

One of his most famous works, Ihyā’ al-sunna wa ikhmād al-bid’a (“Reviving the Prophetic Tradition and Eradicating False Innovation”), was completed before 1773, cementing Usman’s reputation as an intellectual and religious leader.

Over the years, Usman wrote more than 50 books, many of which criticized the local scholars for their superficial interpretations of Islam.

His writings advocated for a return to authentic Islamic values and rejected false innovations in religious practices.

Shehu Usman Dan Fodio Call to Islam (1774-1790s)

Preaching and Religious Reform:

In 1774, Shehu Usman Dan Fodio began his itinerant preaching as a Mallam and continued for twelve years in Gobir and Kebbi, followed by another five years in Zamfara.

Among his notable students were his younger brother Abdullah, the Hausa King Yunfa, and many other influential figures.

Usman’s preaching journey took him to places like Faru and beyond. After returning from Faru, he extended his travels to Illo across the Niger River and Zugu, located beyond the Zamfara River valley.

Criticism of the Ruling Elite:

Usman’s teachings strongly criticized the ruling elite, condemning them for enslavement, idol worship, sacrificial rituals, overtaxation, and greed.

He also pushed for the strict observance of Maliki fiqh, especially in personal observances, commercial law, and criminal law.

Usman denounced practices like the mixing of men and women, pagan customs, dancing at bridal feasts, and unfair inheritance practices that went against Sharia principles.

His message resonated deeply with the peasants and lower classes, leading to massive followership.

Over time, he distanced himself from the royal court and leveraged his growing influence to establish a religious community in Degel, his hometown, which he envisioned as a model Islamic town.

He spent 20 years there, focusing on writing, teaching, and preaching.

Mystical Influence and Visionary Experiences:

In 1789, Usman experienced a mystical vision that led him to believe he had the power to work miracles.

This event inspired him to teach his own mystical word (litany), which is still practiced in the Islamic world today.

During the 1790s, Usman had further visions of Abdul Qadir Gilani, the founder of the Qadiriyya tariqah.

These visions marked his initiation into the Qadiriyya and his spiritual connection with the Prophet Muhammad.

Usman later became the head of his Qadiriyya brotherhood, calling for the purification of Islamic practices.

Theological Writings and Renewal:

Usman’s theological works delved into the concepts of the mujaddid (renewer) and the role of the Ulama in teaching history.

His writings were primarily in Arabic and Fulfulde (Fula language), and they addressed key issues of Islamic renewal and societal transformation.

Shehu Usman Dan Fodio Notable Works

Shehu Usman Dan Fodio wrote more than a hundred books covering diverse topics such as economy, history, law, administration, women’s rights, government, culture, politics, and society.

He authored 118 poems in Arabic, Fulfulde, and Hausa languages. Below is a list of his notable works:

Key Works:

1. Usul al-`Adl (Principles of Justice)

2. Bayan Wujub al-hijrah, Ibad (Description of the Obligation of Migration for People)

3. Nur al-Ibad (Light of the Slaves)

4. Najm al-Ikhwan (Star of the Brothers)

5. Siraj al-Ikhwan (Lamp for the Brothers)

6. Ihyā’ al-sunna wa ikhmād al-bid’a (Revival of the Prophetic Practice and Obliteration of False Innovation)

7. Kitab al-Farq (Book of the Difference)

8. Bayan Bid`ah al-Shaytaniyah (Description of the Satanic Innovations)

9. Ādāb al-‘ādāt (Ethics of Customs)

10. Ādāb al-ākhira (Ethics of the Hereafter)

11. ‘Adad al-dā’i ilā al-dīn (Number of the Callers to the Religion)

12. Akhlāq al-mustafā (Ethics of the Chosen One)

13. Al-abyāt ‘alā ‘Abd al-Qādir al-Jīlānī (Verses on Abd al-Qadir al-Jilani)

14. Al-amr bi-al-ma’rūf wa-al-nahy an al-munkar (Enjoining the Good and Forbidding the Evil)

15. Al-‘aql al-awwal (The First Intellect)

16. Al-jihād (The Jihad)

Many of his works were focused on Islamic ethics, political reforms, and social justice.

His works played a pivotal role in shaping the Islamic intellectual landscape of the time and influencing generations of scholars and reformers.

Reforms by Shehu Usman Dan Fodio: A Comprehensive Overview

Women’s Rights and Education:

One of the most revolutionary actions taken by Shehu Usman Dan Fodio at the beginning of his mission was his focus on the mass education of women.

The Shehu (leader) criticized the ulama (Islamic scholars) for neglecting women, referring to this as a grave injustice, leaving them “abandoned like beasts” (Nur al-Albab, p. 10, quoted by Shagari & Boyd, 1978, p. 39).

In response to objections raised by Elkanemi of Borno, Shehu Usman Dan Fodio strongly advocated for women’s education, asserting that women should receive the same level of education as men (Shagari & Boyd, 1978, pp. 84–90).

He not only educated his sons but also his daughters, who later continued his mission.

His daughter Nana Asma’u was especially prominent, translating her father’s works into local languages, which was groundbreaking at the time.

By including women in the same educational settings as men, Shehu Usman Dan Fodio introduced a radical shift in educational norms.

Economic Reforms:

The Shehu was highly critical of the Hausa ruling elite for their heavy taxation and their disregard for Islamic law.

He condemned various forms of oppression, including the giving and acceptance of bribes, unjust taxation, and the unlawful seizure of land.

He argued that the poor should not be oppressed and that the state’s resources should not be misused (Shagari & Boyd, 1978, p. 15).

His followers were encouraged to learn a craft and earn a living through their own efforts, emphasizing the importance of hard work over idleness (Shagari & Boyd, 1978, p. 18).

Shehu Usman Dan Fodio’s economic vision was centered on Islamic economic principles.

He advocated for the revival of Islamic institutions such as al-hisbah (market oversight), hima (communal land management), bayt al-mal (state treasury), Zakat (almsgiving), and Waqf (endowment).

His economic ideas are detailed in his works, including Bayan Wujub al-Hijrah and Kitab al-Farq.

Economic System and Ethics:

Shehu Usman Dan Fodio’s economic philosophy was built on values such as justice, sincerity, moderation, and honesty.

He emphasized that justice was the cornerstone of progress, while injustice led to societal decline (Dan Fodio, 1978, p. 142).

The Shehu cautioned against harmful practices like fraud, extravagance, and adulteration, which he believed could have devastating consequences for the economy (Dan Fodio, 1978, p. 142).

He also promoted fair market functioning, advocating for the Hisba institutions to regulate market prices, ensure quality control, prevent fraud, and combat monopolies (Kani, p. 65).

The Shehu’s stance on public expenditure reflected his dedication to justice.

He recommended spending on defense and armaments, followed by allocations to judges and state officials, and investment in the construction of mosques and bridges.

Any surplus should be distributed among the poor, and if any remained, the Emir could choose to keep it for future emergencies (Gusau, 1989, pp. 144–145).

Land Reforms:

In terms of land ownership, Shehu Usman Dan Fodio declared that all lands belonged to the state and were to be regarded as Waqf (communal property).

While the Sultan or Emir could allocate land to individuals or families, it could not be sold, and taxation on land was introduced.

This reform aimed to prevent the exploitation of land and to ensure fair distribution.

Shehu Usman Dan Fodio: Background to the Jihad

Origins and Foundation (1780s–1790s):

Shehu Usman Dan Fodio’s rise to prominence began in the 1780s, when his reputation grew due to his appeal to justice and morality, particularly among the outcasts of Hausa society.

His followers included Hausa peasants, slaves, preachers, and pastoralists, all of whom had suffered under the heavy hand of the ruling elite.

These groups were soon joined by Toureg, Fulbe, and Fulani pastoralists, who had faced high taxes and the seizure of their cattle (Shagari & Boyd, 1978, p. 39).

In 1788–89, the power of Gobir began to decline as the Shehu’s influence grew.

The Sultan of Gobir, Bawa Jan Gwarzo, attempted to suppress Usman’s movement, but Dan Fodio’s influence only spread further.

In 1804, after several confrontations, the Shehu declared his Jihad in response to continued oppression.

The Jihad aimed not only at religious reform but also at the unification of various groups under one religious-political ideology.

The Jihad and the Five Concessions:

In 1804, the Sultan of Gobir, fearing Usman dan Fodio’s growing influence, summoned him to Magami during Eid al-Adha. Usman managed to secure five concessions from the Sultan:

Freedom for all prisoners.

1. Respect for anyone wearing the Turban (a symbol of the Shehu’s Islamic Community).

2. Freedom to call on God.

3. Freedom for followers to respond to the call.

4. Tax exemptions for his followers.

These concessions laid the groundwork for the Jihad, which led to the Islamic revolution in the region and the establishment of a new political order.

NOTE: Shehu Usman Dan Fodio’s reforms in education, economics, land ownership, and social justice had a profound and lasting impact on the region.

His commitment to equality, justice, and ethical governance inspired his followers and left an enduring legacy in the history of Islamic West Africa.

His vision of a just and moral society, where women were equally educated and economic opportunities were available to all, remains influential to this day.

Conflict with Nafata and the Decline of Gobir’s Power:

After the death of King Bawa of Gobir, the power of the Gobir kingdom began to decline due to continuous battles with neighboring states.

In the ensuing conflict, Yaaqub, the son of Bawa, was killed in battle, further escalating tensions between Gobir and Zamfara.

Additionally, Ali Al-Faris, the leader of the Alibawa Clan of the Fulani in Zurmi, was killed by the Gobirawa.

This event led the Alibawa to eventually join forces with Shehu Usman dan Fodio.

Similarly, the Zamfarawa, who had recently been subdued by the Gobirawa, rebelled once more.

King Nafata, the ruler of Gobir at the time, lacked the power to suppress these uprisings, and the Shehu gained considerable followers at the expense of the Sultan’s authority.

Nafata’s Actions Against Islamic Practices (1797–98):

In 1797–98, Nafata, in an attempt to weaken the Shehu’s influence, took drastic actions by delegalizing certain Islamic practices.

He prohibited Shaykhs from preaching, banned the Islamic community from wearing turbans and veils (Hijab), and made conversions to Islam illegal, ordering converts to revert to their previous religions.

These measures marked a reversal of the policies enacted by Nafata’s predecessor, Bawa, a decade earlier.

Shehu Usman Dan Fodio strongly opposed these actions, writing in his book Tanbih al-Ikhwan ‘ala away al-Sudan (“Concerning the Government of Our Country and Neighboring Countries in Sudan”): “The government of a country is the government of its king without question.

If the king is a Muslim, his land is Muslim; if he is an unbeliever, his land is a land of unbelievers. In these circumstances, anyone must leave for another country.”

The Assassination Attempt on Usman dan Fodio (1802):

In 1802, Yunfa, Nafata’s successor and a former student of Usman, turned against him.

He revoked the autonomy of Degel and attempted to assassinate Usman at Alkalawa.

During the failed attempt, Yunfa captured several of Usman’s followers. In the aftermath, Yunfa sought assistance from other Hausa leaders, warning them that Usman might trigger a widespread jihad.

By the end of Yunfa’s first year of rule, he faced rebellion from Zamfara, an invasion by Katsina, and unrest within the Muslim community, which was increasingly gaining power under the Shehu’s moderation.

The crisis escalated when a Gobir expedition returning to Alkalawa with Muslim prisoners passed through Degel, a region largely controlled by Muslims.

Yunfa, though not directly in charge of the expedition, could not ignore the challenge and ordered an attack on Usman.

The forces attacked Gimbana, capturing Muslims as prisoners.

The Hijra (Exile and Emigration):

At this point, Shehu Usman Dan Fodio wrote Masa’il muhimma, emphasizing the obligation of emigration for persecuted Muslims.

Faced with the threat of attack from Gobir, the Muslim community began their flight from Yunfa’s forces.

They embarked on a difficult journey to Gudu, located about 60 miles away, taking around four to five days to reach safety.

While not everyone could make the journey, some, like the Tuareg scholar Agali, carried Usman’s books on camels and donkeys and returned to assist with the evacuation.

After fleeing Degel, more Muslim communities from across Hausaland joined Usman’s migrating entourage.

Muhammad Bello, Usman’s son, traveled to Kebbi and other neighboring states, distributing pamphlets urging Muslims to join the emigration (Hijrah).

During this period, the book Wathiqat ahl-Sudan was circulated, providing guidance on Islamic law and outlining the actions Muslims were required to take as individuals and as a community.

The King of Gobir, fearing the depopulation of his kingdom, attempted to stop the emigration by harassing the refugees and confiscating their belongings, but these efforts were unsuccessful.

Notable Companions of the Shehu:

Among the key figures accompanying Usman during this tumultuous period were his father, Muhammad Fodiye, his elder brother, Ali, and his younger brother, Abdullahi.

One of Usman’s closest companions, Umar Al-Kammu, played a significant role, especially during the assassination attempt by Yunfa.

Al-Kammu was regarded as third in importance, after Abdullahi and Muhammad Bello, in greeting Usman as the Commander of the Believers.

He also served as a treasurer during the Jihad. Al-Kammu participated in the Battle of Tsuntsua but passed away before Usman in Birnin Fulani near Zauma.

His remains were later brought to Sokoto, where he was buried near the Shehu.

Scribes, Imams, and Other Notable Figures:

In the book Raud Al-Jinan, 17 scribes are mentioned, including the chief scribe, Al-Mustapha.

Two scribes are identified as “Al-Maghribi,” suggesting a North African origin, and another, nicknamed “Malle,” indicating Malian ancestry.

Imams such as Muhammad Sambo, who died in the Battle of Tsuntsua, and Muezzin Ahmad Al-Sudani, who died early in Sarma during the Jihad, are also highlighted.

Other notable figures include Muhammad Shibi, M. Mijji, and Yero, among others.

The Losses in the Jihad:

At the Battle of Tsuntsua, it is reported that 2,000 people died, including 200 memorizers of the Quran.

Outside Usman’s immediate circle, 69 other scholars were mentioned, with about a third of them likely being Fulani or having Fulani names.

The majority of the scholars were connected to the Sokoto region, while others had no clear connection to the area.

This period of conflict and migration shaped the course of the Jihad and the rise of the Sokoto Caliphate under Shehu Usman Dan Fodio, ultimately leading to the establishment of a new Islamic order in Hausaland.

Declaration of Jihad: Emergence as the Commander of the Believers:

With negotiations between the Muslim Community and Gobir at an impasse, an attack was imminent.

The Muslims prepared their defenses and elected a leader.

Abdullahi dan Fodio’s name was proposed, along with alternative candidates Umar Al-Kammu and Imam Muhammad Sambo, the latter being Muhammad Bello’s choice.

Usman’s followers conferred upon him the title “Commander of the Believers” (Amīr al-Muʾminīn) and elected him as the leader.

Additionally, the title “Sarkin Muslim” (Head of Muslims) was granted to Usman. Abdullahi dan Fodio gave the first salute of allegiance, followed by Muhammad Bello.

Although Danfodio was aged (50 years) and weak, preventing him from participating in the fighting, his role remained ceremonial (p. 24).

By April of the same year, the Muslim community, mobilized in Gudu, prepared to face the approaching cavalry of Gobir.

The call for Jihad spread widely across Hausaland and beyond, as seen in a poem by a Bornu scholar:

Verily, a cloud has settled on God’s earth

A cloud so dense that escape from it is impossible

Everywhere from Kordofan and Gobir

And the cities of the Kindin (Tuaregs)

Are settlements of the dogs of Fellata (Bi la’ila)

Serving God in their dwelling places

(I swear by the life of the Prophet and his overwhelming grace)

In reforming all districts and provinces

Ready for future bliss

So, in the year 1214, they are following their beneficent theories

As though it were time to set the world in order by preaching

Alas! that I know all about the tongue of the fox.

Borno Scholar:

That year, Shehu Usman Dan Fodio declared the Jihad and founded the Sokoto Caliphate.

By then, Usman had gained a large following among the Fulani, Hausa peasants, and Tuareg nomads.

His influence made him both a political and religious leader, with the authority to declare and pursue jihad, raise an army, and become its commander.

Uprisings spread throughout Hausaland, with leadership composed largely of Fulani and peasant Hausa, who felt oppressed and over-taxed by their rulers (p. 23).

After declaring Jihad, Usman gathered a force of Hausa warriors to confront Yunfa’s army at Tsuntua.

Yunfa’s forces, consisting of Hausa soldiers and Tuareg allies, defeated Usman’s troops, killing about 2,000 soldiers, including 200 hafiz (memorizers of the Quran).

However, Yunfa’s victory was short-lived, as Usman soon captured Kebbi and Gwandu the following year.

The jihad’s influence spread throughout Hausaland, reaching areas like Kano, Daura, Katsina, Zaria, Borno, Gombe, Adamawa, and Nupe.

The Battle of Tabkin Kwotto:

The first skirmishes saw a small group of Gobir soldiers beaten back (p. 24).

The Muslims then captured Matankari and Konni, two critical towns on their northern flank.

The division of the booty did not follow Islamic law, prompting the Shehu to appoint Umar Al-Kammu as treasurer.

The Muslim community was warned of Yunfa’s cavalry first by a Tuareg nomad and later by fleeing Fulani soldiers from Yunfa’s army.

Yunfa initially sought an alliance with the Sullubawa before continuing.

Muhammed Bello described the cavalry as being about 100 strong, mainly composed of Tuaregs, Sullubawa, and Gobirawa, while Danfodio’s forces included Hausa, Fulani, and Konni Fulani providing local support, with Tuaregs under Agali and Adar Muslims, including the son of the Emir of Adar (p. 27).

The Battle of Tabkin Kwotto took place in Rabi’ al-Awwal 1219 (June 1804 C.E.).

Yunfa’s heavily armed Gobir forces confronted the smaller, ill-equipped Muslim army under Abdullah.

Despite being smaller and poorly armed, the Muslims gained an advantage from the terrain, flanked by a river and thick forest.

The morale was also high, as the Muslims were determined to avoid capture.

The battle commenced around midday with an assault by Abdullah, evolving into intense hand-to-hand combat with axes, swords, and short-range archery.

By noon, the Gobir forces began to retreat, with Yunfa fleeing the battlefield.

This victory boosted the morale of the Muslim community.

Abdullah subsequently sent letters inviting others to join the victorious forces, receiving a large influx of reinforcements from those initially hesitant.

Food Scarcity:

The rains of 1804 had started, but food supplies before the harvest were still scarce.

Local villagers were hostile and unwilling to sell maize to the Muslims.

As food sources dwindled, the Muslims had to move to new areas.

According to Murray Last, the campaigns of the Jihad were driven, in part, by the search for food, as well as pasture and water for cattle.

After the success at Tabkin Kwotto, several local kings began to align with the Shehu, notably the leaders of Mafara, Burmi, and Donko.

Only the Sarki of Gummi in southwestern Zamfara continued to support Gobir.

These kings had known the Shehu during his preaching tours in Zamfara and sent traders with food to the Muslim community.

However, according to Muhammad Bello, their allegiance was more due to their hostility toward Gobir than any genuine adherence to Islam or reform (p. 27).

Despite this, food scarcity remained a significant issue, and the peasants were losing patience.

The Battle of Tsuntsua:

In October 1804, after the harvest, the Muslims began their aggressive campaign.

They moved out of the valleys into scrubland, where they were safer from cavalry attacks and had more freedom of movement. Their first major objective was the Gobir capital, Alkalawa.

The Muslims gained several allies, and Gobir forces started to target their Sullubawa allies.

In southeastern Gobir and old Zamfara, Muslims found additional allies among the Alibanawa Fulani, who had suffered under Gobir’s rule.

During Ramadan, while the Muslims were dispersed searching for food, Yunfa’s army launched a counterattack at Tsuntsua, two miles from the capital.

According to Muhammad Bello, the Muslims lost about 2,000 men, 200 of whom were hafiz.

Both Muhammad Bello and Abdullahi dan Fodio were injured, with the former being sick and the latter wounded in the leg.

Among the dead were relatives of the Shehu, including Imam Muhammad Samo, Zaid bin Muhammad Sa’ad, and Mahmud Gurdam.

Following their defeat at Tsuntsua, the Muslims remained in the valley until after Ramadan and then began upriver toward Zamfara in search of food.

The Capture of Kebbi:

The Muslims established friendly relations with local groups in southern Zamfara.

Although the Zamfarawa were largely pagans, they were more hostile to Gobir than to the Muslims, having previously suffered from Gobir’s conquests.

The campaign against Kebbi began, with Abdullahi and Ali Jedo leading the forces.

The Kebbi capital was captured, and the Kebbawa fled north.

The strategic importance of Kebbi lay in its proximity to Gwandu, enabling further advances and the establishment of a permanent Muslim base there.

This secured a stable foothold for the Muslims, allowing them to continue their fight against Gobir with reduced risks of further defeats (p. 34).

Check Out: General Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida: Nigeria’s Military Leader and Head of State (1985–1993)

Shehu Usman Dan Fodio The Battle of Alwassa (1805)

Soon after the Muslims arrived at Gwandu in 1805, they were attacked by a coalition of Gobirawa, Tuareg, and Kebbawa pagan forces.

Despite losing about 1,000 men (according to Muhammad Bello), the Muslim forces eventually gained the upper hand.

The rugged terrain around Gwandu worked to their advantage, especially against the Tuareg camels, which struggled to navigate the landscape.

The Muslims successfully repelled the invaders, marking an important early victory in the Sokoto Jihad.

Shehu Usman Dan Fodio Expansion of the Jihad (1804–1812)

Following the defeat of Gobir, panic spread among many Hausa kings and chiefs. Fearing a similar fate, they began to persecute Islamic communities within their domains.

A commercial embargo was placed on Gudu, isolating the town and increasing pressure on the Shehu (Usman ɗan Fodio) and his followers.

At this point, Zamfara’s alliance with the Shehu became vital.

Although Zamfara’s support was more politically motivated due to their rivalry with Gobir than religious devotion, it still offered a crucial respite.

After the Battle of Kwotto, it became clear that the jihad had evolved beyond self-defense.

It was now a mission to preserve and spread Islam against Hausa rulers bent on destroying it.

In response, Shehu Usman ɗan Fodio appointed 14 commanders, dispatching them to lead their people in jihad across Hausa territories.

This action triggered a widespread Islamic revival throughout Hausa land and parts of Borno.

By 1808, the jihadists had defeated major Hausa kingdoms, including Gobir, Kano, and Katsina.

Within a few short years, Usman ɗan Fodio became the spiritual and political leader of the vast Sokoto Caliphate, the largest state in sub-Saharan Africa at the time.

Shehu Usman Dan Fodio: Establishment of the Sokoto Caliphate (1812)

In 1812, the caliphate’s administration was restructured. Shehu Usman Dan Fodio, Muhammad Bello assumed leadership in the eastern regions, while his brother, Abdullahi Dan Fodio, took charge of the western territories.

This system ensured effective governance while continuing the jihad’s momentum. Usman himself stepped back from military and political affairs, dedicating his time to Islamic scholarship and teaching.

Shehu Usman Dan Fodio: Islamic Governance and Reforms

The Sokoto Caliphate merged Islamic governance with a reformed version of the Hausa monarchy. Muhammed Bello introduced:

-

Islamic courts and judges (Qadis)

-

Market inspectors (Muhtasibs)

-

Prayer leaders (Imams)

-

Islamic taxes, including kharaj (land tax) and jizya (non-Muslim poll tax)

Nomadic Fulani herders were encouraged to settle and transition to livestock farming under Islamic law.

The caliphate sponsored the construction of mosques and madrassahs, which spread Islamic education. Arabic, Hausa, and Fulfulde poetry thrived, and Sufism gained widespread influence.

Shehu Usman Dan Fodio Death of Usman ɗan Fodio (April 20, 1817)

In 1815, Usman moved to Sokoto, where his son Bello built him a residence in the western part of the city.

He passed away on April 20, 1817, at the age of 62.

After his death, Muhammad Bello succeeded him as Amir al-Mu’minin (Commander of the Faithful) and the second Caliph of Sokoto.

His brother Abdullahi was made Emir of Gwandu, administering the Western Emirates, including Nupe.

By 1830, the jihad had successfully unified Hausa states, parts of Nupe, and Fulani settlements in Bauchi and Adamawa under a single Islamic state.

Between Usman ɗan Fodio’s era and the British colonization in the early 20th century, the Sokoto Caliphate saw twelve caliphs.

Check Out: Mallam Aminu Kano (1920–1983): Biography, Legacy, Political Influence, and Lessons from His Life

Shehu Usman Dan Fodio Legacy

Encyclopedia Britannica recognizes Shehu Usman Dan Fodio as the most influential Islamic reformer in 19th-century Western Sudan.

He is revered by Muslims as a Mujaddid (reviver of the faith). Many followers supported him because they were disillusioned by Hausa rulers mixing Islam with traditional African religion.

In his famous book Tanbih al-ikhwan ‘ala ahwal al-Sudan, Usman wrote:

“As for the sultans, they are undoubtedly unbelievers, even though they may profess the religion of Islam, because they practice polytheistic rituals and turn people away from the path of God…”

According to David Westerlund in Islam Outside the Arab World, the jihad created a federal theocratic system that allowed regional emirates autonomy, while still recognizing the spiritual authority of the Sultan of Sokoto.

Shehu Usman Dan Fodio strongly opposed:

-

Corruption at all levels of government

-

Excessive taxation

-

Obstruction of trade and business

-

Injustice against common people

He rejected the need for a written constitution, advocating instead for a state governed by the Qur’an, Sunnah, and ijma (consensus of scholars).

Shehu Usman Dan Fodio’s Personal Life

Shehu Usman Dan Fodio was described as tall and lean, standing well over six feet (1.8 meters), and he closely resembled his mother, Sayda Hauwa.

His younger brother, Abdullahi dan Fodio (1761–1829), was also over 6 feet tall (1.83 meters) and was said to look more like their father, Muhammad Fodio, having a darker complexion and later developing a portly physique in his older years.

According to Waziri Gidado ɗan Laima (1777–1851), who chronicled the family in Rawd al-Janaan (The Meadows of Paradise), Usman had multiple wives.

His primary spouse was his first cousin, Maymuna, with whom he had 11 children, including:

-

Aliyu (born in the 1770s – died in the 1790s)

-

Hasan (born in 1793 – died in November 1817), twin brother of:

-

Nana Asmaʼu (born in 1793 – died in 1864) – a revered poet, scholar, and feminist reformer.

Another notable wife was Aisha, ɗan Muhammad Sa’d, also known by her Fulfulde nickname Gaabdo (meaning “Joy”) and Iyya Garka in Hausa (meaning “Lady of the House/Compound”).

She was widely celebrated for her deep Islamic knowledge and became the matriarch of the family.

Aisha lived many years beyond the death of her husband and was the mother of Muhammad Sa’d (1777 – died before 1800).

Shehu Usman Dan Fodio Writings and Intellectual Contributions

Shehu Usman Dan Fodio was a prolific Islamic scholar and writer.

He authored hundreds of works covering various branches of Islamic knowledge, including:

-

Aqeedah (Islamic creed)

-

Maliki fiqh (jurisprudence)

-

Hadith criticism

-

Islamic spirituality and Sufism

-

Poetry and theology

His writings were primarily in Arabic, but he also contributed significantly in Fulfulde and Hausa, making Islamic teachings more accessible to local populations.

In total, he wrote about 480 poems and numerous treatises on religious reform and governance.

Shehu Usman Dan Fodio in Popular Culture

Shehu Usman Dan Fodio’s legacy has transcended academic and religious texts.

In 2020, he was featured as a playable character in the video game Age of Empires III: Definitive Edition, showcasing his role in African history to a global audience of gamers and enthusiasts.

FAQs

1: Who was Shehu Usman ɗan Fodio?

Shehu Usman Dan Fodio (1754–1817) was a prominent Fulani Islamic scholar, teacher, preacher, and reformer who led a religious and social revolution in West Africa.

He founded the Sokoto Caliphate, one of the most powerful Islamic states in pre-colonial Africa.

2: What inspired Shehu Usman Dan Fodio’s jihad (Islamic reform movement)?

Shehu Usman Dan Fodio was deeply disturbed by the corruption, moral decline, and un-Islamic practices among Muslim leaders in Hausaland.

Inspired by Islamic teachings and the need for reform, he led a peaceful movement calling for a return to Qur’anic values, eventually launching a jihad in 1804.

3: What was the Sokoto Caliphate?

The Sokoto Caliphate was an Islamic empire established by ɗan Fodio after his successful jihad.

It became the largest and most influential Islamic state in West Africa, covering parts of present-day Nigeria, Niger, and Cameroon.

4: What was Shehu Usman Dan Fodio’s main religious school of thought?

Shehu Usman Dan Fodio was a Sunni Muslim, following the Maliki school of jurisprudence.

He was also part of the Qadiri Sufi order and adhered to the Ash’ari creed.

5: What are some of Shehu Usman Dan Fodio’s most important works?

He authored over 100 scholarly works, including texts on:

-

Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh)

-

Hadith

-

Tafsir (Qur’anic commentary)

-

Poetry and mysticism

-

Reformist treatises

Notable titles include:

-

Bayan Wujub al-Hijrah ‘ala al-‘Ibad

-

Kitab al-Farq

-

Diwan (Poetry collections)

6: In what languages did Shehu Usman Dan Fodio write?

Shehu Usman Dan Fodio wrote in Arabic, Fulfulde, and Hausa. He is one of the earliest scholars to elevate African languages in scholarly Islamic writing.

7: Who were Shehu Usman Dan Fodio’s most famous children?

-

Muhammad Bello – His successor and the first Sultan of Sokoto.

-

Nana Asma’u – A celebrated poet, scholar, and women’s education pioneer in West Africa.

8: What was Shehu Usman Dan Fodio’s influence on education?

Shehu Usman Dan Fodio revolutionized Islamic education by encouraging literacy among men and women. He believed knowledge should be accessible and promoted female scholarship, which was rare at the time.

9: What is Shehu Usman Dan Fodio’s legacy today?

Shehu Usman Dan Fodio remains a revered figure in Islamic and African history. His legacy is seen in:

-

The enduring Islamic scholarship of Sokoto

-

The integration of Islamic governance in Nigerian history

-

His advocacy for social justice and women’s rights through education

10: Where is Shehu Usman Dan Fodio buried?

He is buried at Hubbare Shehu in Sokoto, Nigeria, a site that remains a place of historical and spiritual significance.

Conclusion

Shehu Usman ɗan Fodio (1754–1817) stands as one of the most influential Islamic scholars and reformers in West African history.

Through his deep knowledge of Islamic jurisprudence, his passion for religious and social reform, and his leadership in the Fulani Jihad, he established the Sokoto Caliphate, which became a major center of Islamic learning, governance, and unity.

His legacy lives on not only through his prolific writings and descendants, such as Muhammad Bello and Nana Asma’u, but also through the enduring spiritual and political structures he helped shape.

His emphasis on justice, education, and spiritual renewal continues to inspire scholars and leaders across Africa and the Muslim world.

Check Out: General Murtala Ramat Muhammed: Nigeria’s Boldest Head of State (1975–1976)

Check Out: General Yakubu Gowon: Nigeria’s Youngest Head of State and Civil War Leader (1966–1975)

Check Out: Abubakar Imam (1911–1981): Northern Nigeria’s Pioneer Intellectual and Political Icon